Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Dharma in English

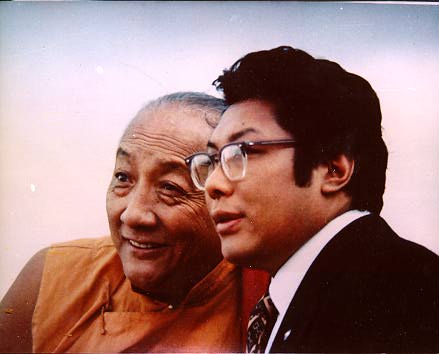

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche is seen here with Dilgo Khyentsé Rinpoche. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s books have had a profound influence on many people. He made it possible for people to gain an understanding, who had previously failed to connect with the real meaning of Dharma in their lives. Ngak’chang Rinpoche has given several short talks at the San Francisco Shambhala Centre on his appreciation of the language of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and what follows is a selection of quotations from these talks:

We have tèn’drèl – auspicious connection – a shared enthusiasm for essential Dharma and a shared openness to cut through spiritual materialism. It is excellent that we are gathered here in a centre established by the Mahasiddha, Rig’dzin Chenpo Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche – the most extraordinary influence on the development and understanding of Vajrayana in the West. He opened a window on the essential meaning and allowed the fresh air of Dharma to enter the mausoleum of our confusion. The window Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche opened was the stained-glass window of spiritual materialism – the stained-glass window of out fascination with Oriental mystery. Dharma was no longer an esoteric hobby divorced from the day-to-day realities of our existence.

I first came across a book by Trungpa Rinpoche in the late 1960s. It was called ‘Meditation in Action’, and it was early enough in my training for me to have made the joyfully naïve assumption that ‘This is the way in which Dharma will be expressed in the West from now on!’ The language by which means I had received Dharma up until that point had been somewhat akin to the ‘biblical’ style exemplified by Evans-Wentz – and it therefore came as a significant relief to discover that pietistic linguistics were not necessary.

The language in which I had to study Dharma in the 1960s was convoluted in a mediæval sense – so when I came across Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s books in the 1970s I was joyously shocked by the possibility of speaking in English. I have been invited to teach at various Buddhist groups in Bath, Raglan, and Cardiff and I was aware that the knowledge level of my audiences was rudimentary. It was thus important to be able to explain Dharma to students in a way that brought the subject alive for them. Reading Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s books gave me permission to speak naturally in English; and I have been speaking and writing in contemporary English ever since. It is not particularly that I have adopted Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s individual contemporary style of English—no one would confuse our written material in any case—but I have attempted to use an English that the averagely educated person would understand. I have also employed—as Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche did—analogies directly related with the everyday lives of students.

I always remember Trungpa Rinpoche as one of my Lamas, even though I never met him. His inspiration has been such that it has permeated the lives of many people. When I started teaching in l979 I was not really sure how to express things to the people who invited me to teach – and so I owe an immeasurable debt of gratitude to Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche for liberating me from reliance on anachronistic formulæ. I had listened to various Western people present Dharma at Buddhist establishments and had assumed that there existed an accepted protocol with regard to how Dharma should be conveyed. It seemed to me that the entwining of academic patois and Asiatic Shakespearianism did little to make Vajrayana comprehensible. It seemed to me that the secrecy of Vajrayana did not need to be further enshrouded by language that denied access. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s approach to explaining Vajrayana on the other hand employed a precise and direct sentence structure which took his audience straight to the heart of the teaching. His published presentations were forthright communications in which it was always clear that the only barrier to comprehension was the experiential level of the listener or reader.