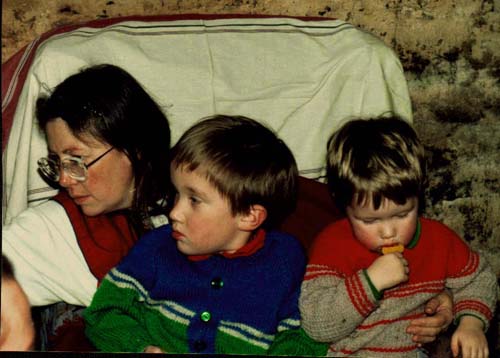

Ngala Nor’dzin

with sons Daniel & Richard

Ngala Nor’dzin and Ngala ’ö-Dzin have been Vajrayana practitioners from the beginning of their relationship. They met at a Buddhist centre in Raglan, Gwent, Wales – on the first Tibetan Buddhist retreat Ngala Nor’dzin attended. Their children have consequently grown up in a Buddhist household throughout their lives. In this picture Ngala Nor’dzin is seen with Daniel and Richard at a retreat when they were quite young – about five years and three years old.

Ngala Nor’dzin says:

We have always tried to avoid indoctrinating our children. They are surrounded by the atmosphere and energy of our practice as the fabric of our everyday lives, but we do not demand any formal involvement from them.

Ngak’chang Rinpoche and Khandro Déchen tell parents that if they are worthy of emulation that their children will naturally emulate them – and if not they will not. They point out that trying to make children practice can merely cause them obstacles in relation to practice – whereas living the view will undoubtedly inspire them.

Ngala ’ö-Dzin says:

They enjoy singing

Dorje tsig-dun before meals, and they sometimes surprise us when we find one or other of them sitting quietly with their teng’ar reciting mantra.

Daniel and Richard have received information on other religions at school, and that has sparked many interesting discussions.

Ngala Nor’dzin comments:

Sometimes our children teach us so much by the questions they ask. We have to try to answer them in a way which will be understandable to them. This helps us a great deal in teaching adults. We never pretend to be confident about areas of knowledge in which we lack ‘actual experience’ – areas such as the process of death and taking re-birth.

Ngala Nor’dzin and Ngala ’ö-Dzin believe that their children need the opportunity to find and choose Buddhism in their own way, as they themselves had done.

Ngala ’ö-Dzin comments:

Both Daniel and Richard describe themselves as Buddhists when asked, and are proud of their refuge names. Daniel—when he was quite young—told me very earnestly that he will probably not want to be ordained when he grew up, but that he would ‘practice regularly and go to a few retreats a year’. We find such statements heart warming, but we still remain open and fluid about our sons’ place in the Vajrayana lineage for which we have taken responsibility. It is more important to us that our children grow up to be happy, well-adjusted, kind individuals, than it is that they necessarily become ordained into the

gö kar chang-lo’i dé of the

Aro gTér lineage.